Hey everyone!

Today’s blog has been written by

OxNav, who are a group of student researchers based on Skomer, studying the

ecology and navigational strategies of Skomer’s hidden gems, the Manx

shearwaters!

For those who may be unfamiliar

with Manx shearwaters, or Manxies as we fondly call them, they are a species of

Procellariform seabird which spend the majority of their lives out at sea, but

return to burrows on islands around the UK, such as Skomer, during their summer

breeding season to reunite with partners, lay eggs, and raise their chicks.

Skomer Island is home to the world’s largest colony of Manxies, an impressive 350,000 pairs, which makes up 40% of the world’s population! Here at OxNav we study breeding pairs in one of the densest parts of the island, North Haven. For those of you who have visited Skomer, you have likely gazed across our study colony without realising, we face out of North Haven bay, where the boats land, and our colony spans the hills all around the warden’s house, with hundreds of burrows marked and hatched for easy access into the nesting chamber.

|

| Above: An adult Manx shearwater sat on the surface at night. Below: Lewis and trusty friend Alice checking study burrows for the arrival of an egg. |

This year, we arrived on Skomer with the Manxies, all the way back in the beginning of April, when the first adults returned from their grand migration to Argentina to reunite with their partners. However, getting here as early as we did this year revealed that perhaps these pair-bonded seabirds aren’t as loyal as we once thought they were! We found that many birds would spend the night cwtched up in a burrow with a bird other than their usual partner, only to then go back and recouple with said partner later in the season, I guess the grass wasn’t greener in the other burrow for these birds! But this posed an interesting theory, how can a male ensure that he is the father of the chick he raises? Do perhaps males with a greater drive to defend their burrows (and in-turn their partner) have a greater chance of being the biological father? Sounds to us like a job for Jeremy Kyle…

|

| A breeding pair of Manx shearwaters spending the night together in their burrow. |

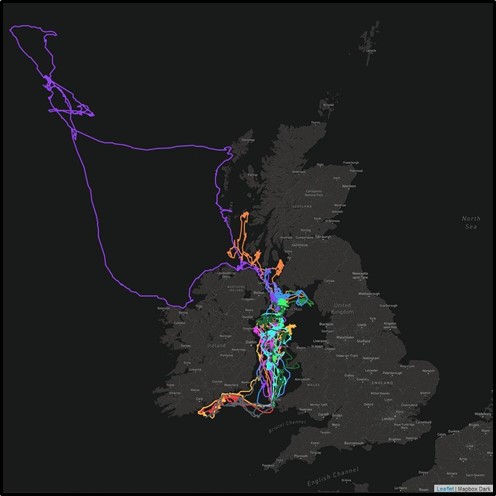

Once these dramatic revelations had passed and eggs had been laid, we turned our attention to our incubation tracking campaign! We attached small GPS loggers weighing only 10g to the backs of adult Manxies (picture a little computerised backpack) to track their movements during their at-sea foraging trips. These excursions can last over 10 days, with the birds covering incredible distances in search of food to fuel their next stint of incubating the egg! From these GPS tracks, we can uncover so much about these speedy seabirds: where they go to forage, when and how they make the decision to return home, how they do this with such accuracy, and how all of these wonders vary between individuals.

|

| GPS tracks from incubating Manx shearwaters. Each colour shows a different bird, with one heading far North out into the Atlantic Ocean! |

Now, the moment you’ve all been waiting for… fluffy chicks! From lay to hatch, the parents will incubate an egg for around 51 days, before a bundle of cuteness and downy feathers cracks its way out of the small, white egg. Here at OxNav we are lucky enough to monitor a subset of our colony’s chicks, weighing them every day to gain insight into general colony productivity, potentially revealing seasonal variations in food availability, or perhaps how well the parents are performing in their baby-feeding strategies. Of course this chick monitoring has great scientific value, but personally we love the opportunity to watch these fluffy chicks grow and develop, from a small 50g peeping nugget, to a 650g sacks of flapping wings and teenage angst.

Pictured below is our personal favourite, Megan thee Shearwater, affectionately named after the hip-hop sensation, Megan thee Stallion, representing strong female shearwaters, and all the trouble they go through in producing and laying the egg, you go girls!

|

| From left to right, we see our lovely long-term volunteers: Eve, Kelda, and Lira & Anna, helping to weigh Megan as she grew throughout the season! |

In the past few months, when not cuddling chicks (for science of course), we have been deploying more GPS devices to gain insight into their shorter, more frequent chick-rearing foraging trips. This year we have synchronised deployments across the islands of Skomer, Skokholm, and Ramsey, to see if these colonies overlap in their foraging grounds, or perhaps all occupy separate areas! We also piloted a future study for one of our new PhD students, Lewis (that’s me, hello!), where we displaced GPS-wielding adults to other locations around the island, such as the Mew Stone and Garland Stone, to investigate whether their short-scale navigation is as impressive as in their long-range movements. Here's a little sneak peek for you… it’s looking like the answer is yes! We had birds which seemed to understand their release location very well, knowing the optimal route around the island (since they prefer not to fly over land), and returning to the colony in less than three minutes, now that’s a bird with a built in SatNav if I’ve ever seen one!

|

A Manx shearwater mid take-off during one of the displacement studies. You can see the GPS flashing as the bird is released. |

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading about our work! We love chatting about Manxies (if you couldn’t tell) so drop the team a message through these accounts if we’ve piqued your interest: Instagram - @Lewisthezoologist, Twitter - @LFisherReeves

Lewis & Alana

|

Team Chick-rearing

2022! Alana, Trina, and Lewis, enjoying the sunset together. |

Just to note: With the increasing risk of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) to our seabirds, it’s worth mentioning that all handling pictured was carried out in the months prior to the rising cases. OxNav and the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales have been closely monitoring the situation and abiding by guidance from leading bodies. Unfortunately, all bird handling on Skomer has now been suspended until further notice.